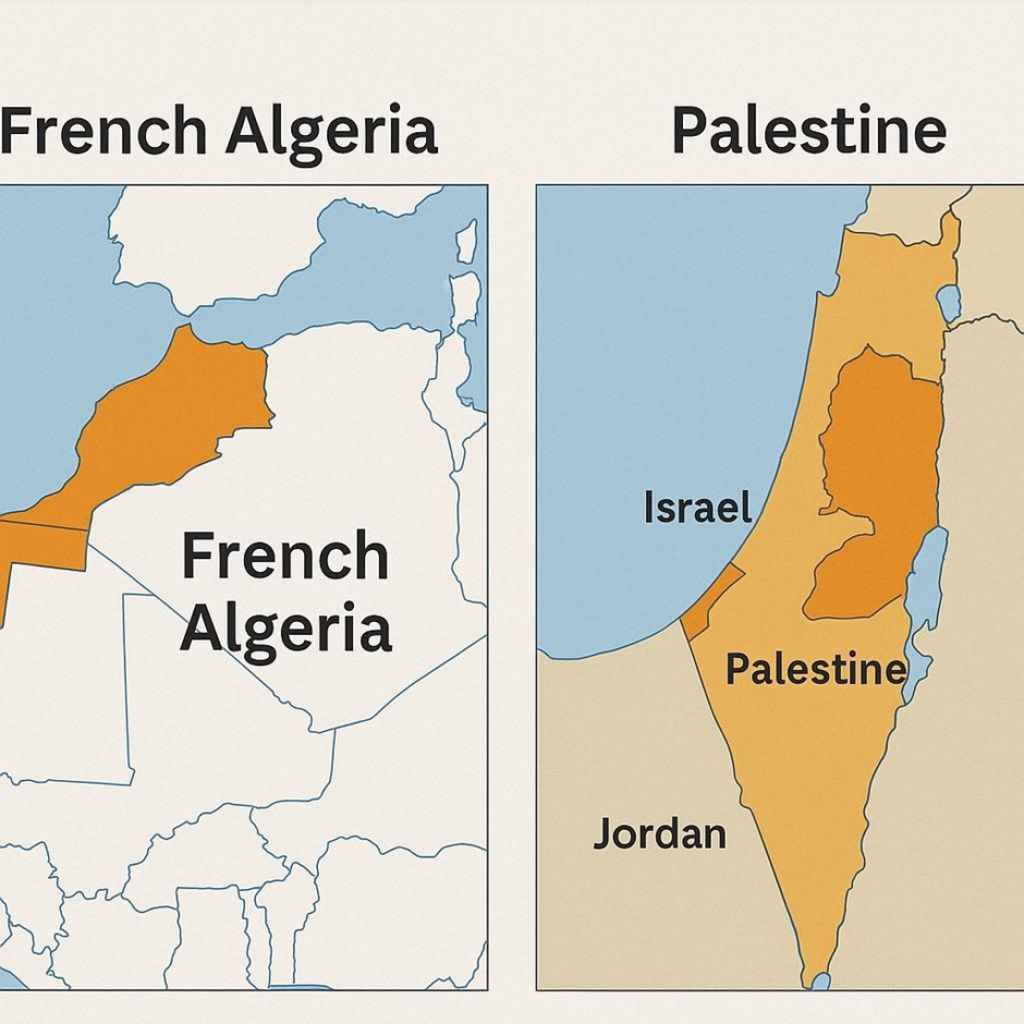

In moments of extreme violence when cities are flattened, populations displaced, and humanitarian language collapses under the weight of mass death, the temptation may be to treat such events as aberrations. It could be perhaps a “war gone too far,” or a “cycle of violence,” or still a tragic breakdown of politics. And yet, history warns us that such interpretations often obfuscate far more than they explain. To understand why French colonisation of Algeria in the 19th and 20th centuries and British-Zionist colonisation of Palestine in the 20th and 21st centuries have endured extraordinary levels of structural violence, we must move beyond the language of conflict into the harder terrain of settler colonialism.

The comparative study of French Algeria and Zionist colonised Palestine is neither an exercise in moral equivalence nor is it an attempt to fuse and ground distinct histories into a monolithic narrative. It is instead an effort to expose a shared political architecture that grounds such violence and organises domination not through any temporary occupation but through permanent replacement. Consequently, what then links these two cases is not ideology, religion, or even geography, but a colonial logic that seeks to erase Indigenous presence in order to make settler sovereignty irreversible. Here, Patrick Wolfe’s theorisation of settler colonialism, insisting that it is not an event but a structure, emerges as indispensable for understanding both histories. Settler colonialism does not arrive, conquer, and depart as some sort of chronological event; but it arrives to stay. But then to stay, it must eliminate and eliminate the indigenous.

Why Algeria and Palestine?

At first glance, French Algeria and the continued Israel occupation of Palestine may appear separated by time, context, and political genealogy. While the French colonial project in Algeria emerged from a classic European imperial project backed by a powerful metropole, in contrast, Zionism was presented as a movement of return, refuge, and national self-determination by a ‘historically’ persecuted people, lacking a conventional imperial centre.

Yet, as Edward Said, the celebrated Palestinian-American postcolonial scholar, argues in The Question of Palestine (1992), this contrast has too often been used to shield Israel from structural comparison, placing Palestine outside the global history of colonialism and instead relegating it to the realm of exceptional conflict. Algeria disrupts this narrative by demonstrating that settler colonialism does not depend solely on racial ideology or metropolitan extraction, but on permanence, demographic engineering, and spatial transformation.

France did not merely rule Algeria; rather, its colonial machinery sought to remake this Arab-African colony as it imagined Algeria as an extension of France itself. It implemented this setter project by seizing indigenous lands, establishing settlements, imposing legal stratification, and violent cultural assimilation. The settlers, or pied-noirs, were not transient administrators but future citizens, whereas the indigenous Algerians were concomitantly reduced to subjects without sovereignty, history, or political destiny.

It is this logic of settler permanence and Indigenous erasure that reappears with striking clarity in Palestine. The claim that Zionism is sui generis collapses when confronted with the material practices of settlement, displacement, renaming, and legal exclusion. Whether these colonial erasures are justified through civilising missions or biblical promises, the outcome remains the same: the Indigenous population becomes an obstacle to be managed, removed, or fragmented.

Settler Colonialism and the Logic of Elimination

Patrick Wolfe’s concept of the “logic of elimination” offers a crucial analytic anchor. Unlike the notion of extractive colonialism which relies on indigenous labour, settler colonialism seeks to replace indigenous societies with a new settler order. While this kind of violence does not always take the form of immediate genocide, it often unfolds through land dispossession, bureaucratic violence, cultural erasure, and legal disappearance.

In Algeria, this logic was operationalised through mass land confiscation, the destruction of communal landholding systems, and the imposition of French law. By the early twentieth century, European settlers controlled the majority of Algeria’s most fertile land, while Indigenous Algerians were pushed into poverty, displacement, and political invisibility. The infamous Code de l’Indigénat formalised this hierarchy, reducing Algerians to a sub-legal status within their own land.

When this is contrast with Palestine, though the elimination may demonstrate a different rhythm but it still follows a familiar pattern. The Nakba (catastrophe) of 1948 was not an unfortunate by-product of a war but a foundational act of settler restructuring of Palestine. It saw over 700,000 Palestinians expelled and turned into refugees, hundreds of villages destroyed, and an entire society rendered stateless. What followed was not closure but the continuation of Nakba in the form of military occupation, settlement expansions, house demolitions, and legal apartheid, which do not constitute any deviations from Zionism but its structural expression.

The insistence on treating 1948 as a closed historical chapter, or the 1967 occupation of remaining Palestinian lands beyond the Green Line, which had served as the de facto border of Zionist Israel (1949-1967), as the beginning of “occupation,” serves a political function: it fragments Palestinian history and obscures the continuity of elimination. Settler colonialism thrives on such fragmentation, turning structures into episodes and policies into accidents.

Zionism and the Settler Colonial Debate

But to frame Zionism as settler colonialism is neither novel nor marginal, as scholars and intellectuals, including Palestinian, anti-Zionist Jewish, and Marxists alike, have identified its colonial character long before the establishment of Israel as a successor state of the British Mandate over Palestine in 1948. What is relatively new is the willingness of Israeli scholars themselves, most notably Ilan Pappé, to name Zionism as a settler project rooted in ethnic cleansing and demographic engineering.

Pappé’s archival work on Plan Dalet and the systematic destruction of Palestinian villages shattered the myth of accidental displacement. His argument is not merely historical but structural: Zionism required the removal of Palestinians to establish a Jewish-majority state. This requirement did not vanish in 1948 and persists in policies that restrict the return of indigenous people, fragment Palestinian geography, and criminalise any form of their resistance.

Opponents of the settler colonial framework often point to Jewish historical ties to the land or the absence of a metropole. Yet settler colonialism does not require racial uniformity or imperial sponsorship. It requires a political project committed to replacing one population with another. In this sense, Zionism represents a form of settler colonialism without a metropole, internally sovereign, self-legitimising, and increasingly militarised.

This distinction may explain its endurance. Whereas France could eventually be pressured, politically, morally, and economically, into leaving Algeria, Israel’s settler project has no external centre to withdraw. The absence of a metropole does not weaken settler colonialism; it intensifies its permanence.

Decolonisation and Its Discontents

Algeria’s independence in 1962 is often, and rightly so, celebrated as a triumph of anti-colonial resistance, but reading the country’s decolonisation process as a clean rupture risks misunderstanding the afterlife of settler colonialism. It is because this independence neither erased the economic, cultural, and psychological scars of 132 years of domination nor resolved the crises of identity, governance, and development that colonialism engineered.

It is this afterlife of settler-colonial experience in Algeria that makes it a crucial lesson for Palestine, as decolonisation is not an event marked by flags and treaties but a prolonged struggle over land, memory, and political possibility. As Fanon (1963) contends, Algeria reminds us that liberation can defeat settler rule but also that the cost is immense and the aftermath fraught.

Palestine, by contrast, represents a settler colonialism that has not yet been forced into retreat. The recent Israeli war on Palestinians in Gaza (2023-2025), the entrenchment of ever-expanding settlement projects across the West Bank and East Jerusalem, and the juridical marginalisation of Palestinian citizens of Israel, distinguished by the Israeli state as Arab Israelis, reveal a system which is moving not toward resolution but toward consolidation of the Zionist colonial project. And when elimination meets resistance, violence escalates.

Why This Comparison Matters Now

The urgency of comparing Algeria and Palestine lies not only in academic clarity but in political responsibility. As Gaza has been reduced to rubble in the two-year war with Israeli aggression continuing despite a ceasefire in place, and the humanitarian language often proving inadequate, there has been a continued temptation in the West, particularly its policy circles, to explain Israeli colonial violence as excessive self-defence or tragic overreach. The settler colonial lens strips away this comfort by revealing violence not as a failure but as a function of the continuing project. In the Algerian case, France, too, claimed civilisation, security, and progress. It, too, portrayed resistance as terrorism and framed mass repression as a necessity. Yet Algeria exposed these claims as hollow in the same way Palestine does today.

It should be however noted that when Palestine is situated within the global history of settler colonialism, this is not done with the premise of denying the Jewish suffering or historical trauma associated with their European experience of the Holocaust. Rather, it is to insist that violent experiences and deep traumas cannot justify permanent domination, and that historical persecution does not grant license for contemporary erasure. As Algeria teaches us, no settler regime, however entrenched it may be, can remain immune to collapse once its moral contradictions become unbearable.

Conclusion: Seeing the Structure

This brings us to the question of what really connects French Algeria and Zionist Palestine? The answer is, it is not simply colonial violence but colonial permanence and the refusal to imagine coexistence outside domination. As settler colonialism does not seek compromise but replacement, it cannot be managed, reformed, or humanised; rather, it can be and ought to be dismantled.

In such a context, as Palestinian American scholar Rashid Khalidi in The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine (2020) argues, recognising Palestine as a settler colonial context does not foreclose political solutions; rather, it clarifies what kind of solutions are meaningful. Just as Algeria required the end of settler sovereignty to begin imagining justice, Palestine cannot be free within structures designed for its elimination. Moreover, while comparison with Algeria does not predict Palestine’s future, it does restore historical possibility, reminding us that structures, however brutal, are not eternal and that Indigenous survival, memory, and resistance remain the most enduring challenge to settler power.

This article is the first in a three-part series examining settler colonialism as a structural and enduring form of domination through a comparative lens. By placing French Algeria and Zionist Palestine within the same analytical framework, the series challenges conflict-centric and exceptionalist readings of Palestine, instead situating it within a global history of colonial permanence and Indigenous resistance. The views expressed reflect the author’s scholarly interpretation and are intended to contribute to critical debate on colonialism, decolonisation, and contemporary geopolitics in the Middle East and beyond.