Introduction: Samir Amin’s Enduring Marxist Lens on the Arab Revolutions

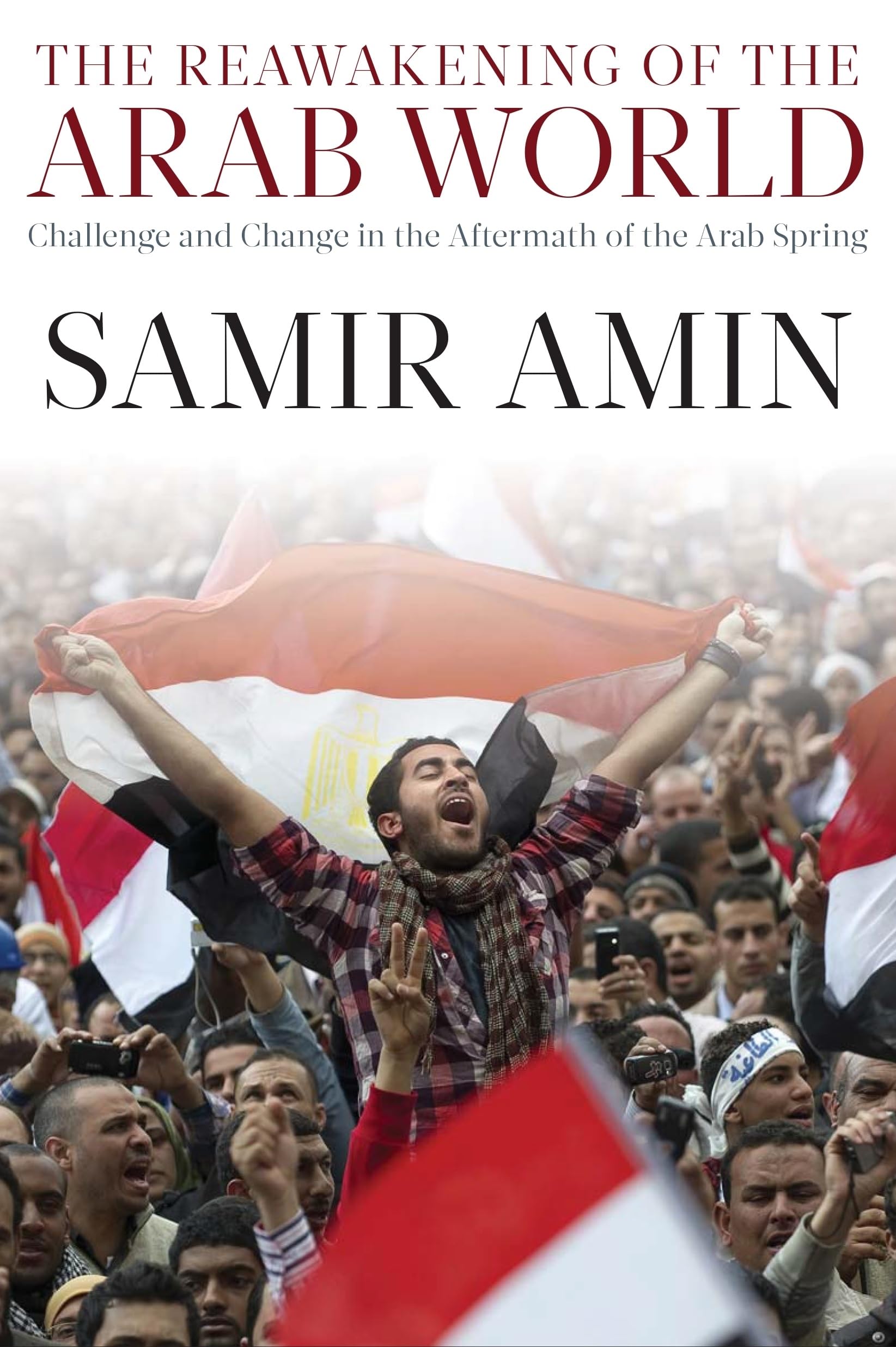

It was 2011 when Cairo erupted in a cry that had been building for decades. It followed similar shouts of hope from the youth, workers, and families in the dusty alleyways of Tunis to the bustling markets of Damascus, calling for isqat al-nizam (topple the regime). The city’s Tahrir Square saw a sea of flags form an ocean of red, white, and black, with the crowd’s raised arms every time a slogan pierced the air, signifying a defiant energy that would subdue only after a new dawn. It is something that is captured in Samir Amin’s The Reawakening of the Arab World: Challenge and Change in the Aftermath of the Arab Spring, not just in its figuratively (cover) but through the words. Picture a man in a checkered shirt, hands lifted high, singing songs of resistance among thousands in downtown Cairo’s ‘Liberation’ Square. It is all-out, it is hopeful, it is human. And that is precisely what Amin — an Egyptian with remarkable foresight who witnessed this — perhaps intended the readers to feel when he wrote the book during the height of the landmark sociopolitical rupture in the Arab world.

Amin’s intervention is not just another dusty textbook: it reads instead like a heartfelt letter of solidarity addressed to the Arab people. It is a letter from someone who has spent his entire life resisting the shadows of inequality. First published in French in 2011, at the very moment the revolts were unfolding across the Arab world, its English edition arrived in 2016 with a reflective ‘afterword’ that looks at what progressed and what faltered. It somehow alludes to why the book’s relevance continues to resonate even to this day, as the region continues to rupture in one way or another. As the wounds of Palestinians in Gaza and across the occupied West Bank remain open, so do those in Sudan.

The Arab Spring, amidst many other global events, seemed to have emerged out of nowhere.

Amin actually tells it in the beginning that “these were not shocks to those who were on the ground.” He is right; the Arab activists had been feeling it coming for several years. And if we go back to the 1950s and 1960s, when the anti-colonial movement in Asia was at its height, countries like Egypt, where Nasser was, and Algeria, which had just fought a war of liberation, and even the new Ba’athist states, Syria and Iraq, were looking the light of day with considerable hope. They weren’t actually full democracies (one-party rule inevitably had its drawbacks), but they were quite real to the commoner. Just imagine: the establishment of free schools and universities gave rise to a new generation of literate professionals, including doctors, engineers, and others. There were clinics in every village, jobs were assured straight after graduation, and the factories were alive with the dream of self-made bright futures. It was social climbing on steroids, all mixed with a strong “no thanks” gesture to the West.

However, the Western empires did not want to be outdone. The West, especially through the wars and economic sanctions, kept these regimes underpinned. When the Soviet Union eventually collapsed in 1991, the door was wide open for what Amin described as the “neoliberal offensive.” The leaders surrendered and swapped their dominion for loans from Western financial institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Then came a sudden disappearance of hard-fought social securities. Schools were slowly closed down, factories gone, and a plethora of retaining walls disappeared into a mist of “flexible” contracts and freelance jobs. By the 2000s, more than 50% of the population in Egypt had been forced to resort to the “informal economy”, where street vendors were running around to avoid being caught by the police, or families were living in one room, sharing it because the rent consumed their entire monthly salary. Poverty was not only a number issue; it was dads coming back home with no money, kids dropping out of school to help the family with trade, and a whole youth who felt like walls of hopelessness surrounded them.

The Bitter Twist: When Elections Gave Power to the Wrong Crowd

Moving ahead to the year 2012, Amin’s postscript gets straight to the point regarding the hangover. Tunisia and Egypt were going to the polls — the “democratic” win that the West applauded — and who came to power? The Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, the Ennahda Movement, and their Salafi supporters in Tunisia. Was this a surprise? Not for Amin. He gives his argument as follows: In a planet where neoliberalism changed civilisations into mere survivors, Islamists found the right tool for survival. They did not sell the people the vision of a glorious future through slow reforms; rather, they proposed grants for the poor and the hungry. In Egypt, where 60% of the population was involved in informal hustling, the Brothers provided micro-loans for vendors, free clinics, and food baskets, using Gulf cash (Qatar and Saudi riyals). It was philanthropy with a bit of ideology: “God will provide if you obey the rules.” It was pretty straightforward, very attractive, and it worked, because who can refuse a meal when their children are starving?

For Amin, the hardest thing to digest was that this was not freedom but a trapdoor. The victory of the Brotherhood entrenched the old army-Islamist pact from Sadat’s era, where the military got the budget, the Islamists got the culture wars, and everyone was under the watchful eye of Uncle Sam. In Tunisia, it was a rehash of the old secularism of the Bourguiba era with an Islamic face; political parties talking, yes, but no real challenge to the rigged economy. Women may lose the battle in the field of rights, and the poor? To square one again, with austerity being the national sport.

The Dark Side of Faith: Unpacking Salafism Without the Fearmongering

When it comes to Salafism, Amin does not mince his words, but without the Islamophobia, often rehashed through cultural products of Hollywood, that the Western world loves. For Amim, Salafis are not merely “extremists” in a vacuum; rather, they are the hard-core section of a more extensive and conservative movement which goes back to the philosophers like Rashid Rida and even the Brothers’ own roots. What is their proposal? Humans are not free; we are God’s “slaves,” as they put it, so democracy is a sin; it’s humans acting as gods. No scope for doubt, imagination, or earthly discussions like “Should workers get a raise?” Rather, it’s the clergy who make the decisions in an Iranian style with a faqih (jurisprudent) as the chief.

Does that sound old-fashioned? Amin, however, points out the contemporary double standard: These people train children in coding and business basics by using the old-fashioned USAID pamphlets from America. Progressivism is not the issue; it is the production of cogs for the capitalist machine that is the case. The Brotherhood plays the “moderation” card to get the thumbs-up from US President Barack Obama while the Salafis do the dirty work of intimidation and division. The result? A fractured and dependent society was kept that way by a one-two punch.

It’s scary, but Amin makes it less so, stating that it is not “Arab DNA” but rather a continuum of reaction to the past humiliation, the oil money, and the Western divide-and-rule policy that have been the factors behind the process.

A Glimmer in Algeria: Can Old Flames Reignite?

Amin concludes his afterword on Algeria with a subtle note, the silent survivor. Like Egypt, Algeria also played a significant role through the independence movement of 1962 and underwent socialist experiments that led to the development of infrastructure, the provision of education, and the instillation of a sense of pride among the people. However, Egypt, after Sadat, went the full comprador route (a fancy term for “local puppets of foreign money”), while Algeria still managed to hold on. Algerian leaders comprised a rather confused and chaotic mixture: some still dreaming of the nation, while others were only interested in easy money from Europe. This division? It was indeed messy, but on the other hand, it also had potential. Reforms were not impossible there, unlike in Egypt, where the elite were locked in.

Imagine it as a contrast between a house that has most of its features deteriorating but still standing on a strong foundation, and the other that has been completely renovated for resale. Algeria’s tale whispers: The Arab world is not a whole that is doomed; it is rather one that is divided, and those fissures are where transformation creeps.

Wrapping It Up: From Fury to Genuine Revolution

Amin certainly does not give readers up to despair. The Arab Spring did not turn out to be a fairy tale fiasco; rather, it was a wake-up call that reminded the world that the power of the people can bring down tyrants, but keeping them down is a matter of confronting the empire that supports them. As such, he calls for a “radical left” that will not only vote but also create: one that will reject the IMF’s nefarious measures and trade with Brazil, India, South Africa, and others in a manner that benefits all parties. It prioritises streets over ballots, for the struggle and not the paper stamp, is what really power is for. Amin’s call continues to resonate as of today across the region amidst the climate chaos causing floods in the Nile Delta, restless youth in Algiers, crisis in Sudan and the broader rupture due to unprecedented Zionist military hegemony.