Recent decades have witnessed a transformation in the notion of national security, wherein conventional military capabilities are increasingly complemented by high-tech defence systems. The face and cost of modern-day conflicts are particularly redefined by advanced air defence capabilities, including sophisticated aircraft, missiles, long-range artillery, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), and radars and interceptors. Conflicts across the globe, from Europe to the Middle East to South Asia, have demonstrated how robust air defence systems (ADS) have become indispensable to a country’s national security, as the aerial dimensions of warfare now play an increasingly central role alongside traditional land and sea operations.

Beyond the traditional arms-exporting powers, states such as Türkiye, India, China, and Israel have positioned themselves as innovators and suppliers of advanced weaponry, particularly in air defence equipment, marking their strategic autonomy, deterrence, and technological prowess in an emerging and uncertain multipolar world order. In this evolving defence landscape, Ankara unveiled its ambitious“Steel Dome” (Çelik Kubbe in Turkish) project in August 2025, officially described as a “system of systems.” Aimed at shielding Türkiye’s national sky, the Steel Dome is a layered-shield design that integrates radars, sensors, and interceptors to neutralise threats from low to high altitudes. Its coverage spans from low-flying drones and rockets within a 5 km range to long-range missiles at altitudes exceeding 20 km.

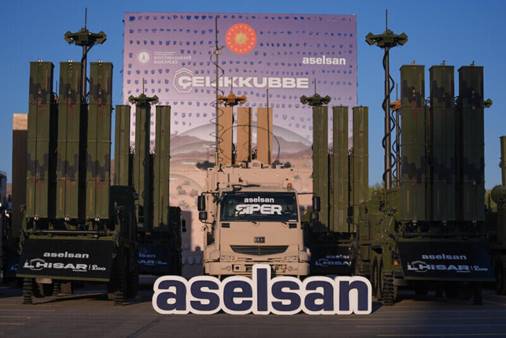

(Image Source: Anadolu Agency)

What is the Steel Dome?

The Steel Dome (Çelik Kubbe), a multilayered air defence system project, was officially endorsed in August 2024 at a meeting of the Defence Industry Executive Committee (SSİK), chaired by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Conceived as a “system of systems”, the Steel Dome constitutes a unified architecture integrating radars, sensors, interceptors, and electronic warfare command-and-control nodes. What makes it particularly distinct is its indigenous development, achieved through the joint efforts of major Turkish defence companies such as ASELSAN, ROKETSAN, TÜBİTAK SAGE, and MKE, along with the support of a network of local firms.

Unlike traditional single-purpose defence equipment, the Steel Dome has been designed as a comprehensive shield to detect, track and neutralise aerial threats across various altitude levels. Some of the systems integrated in this multilayered shield include:

For short-range defence, the Dome features systems such as KORKUT SPAAG (35 mm mobile gun), GÖKDENİZ, GÜRZ, BURÇ, and Göker, primarily aimed at very low-altitude threats, including drones, rockets, artillery, and mortar fire.

For medium-range defence, the Dome includes the HİSAR family (HİSAR-A, HİSAR-A+, HİSAR-O, HİSAR-O+) and MANPADS, such as Sungur, designed to defend against aircraft, helicopters, cruise missiles, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) at higher altitudes and longer ranges.

For long-range purposes, it deploys the SİPER system for high-altitude interception to counter strategic threats such as aircraft and long-range, possibly ballistic missile threats.

Additionally, laser programmes such as ALKA and GÖKBERK, similar to Israel’s “Laser Beam” project, will complement the Steel Dome. It aims to neutralise drones and small projectiles more cost-effectively than using expensive missile interceptors, thus drastically reducing the cost and checking the penetration of any rocket into the Dome.

Apart from missile and laser systems, the Steel Dome is supported by advanced sensor and radar infrastructure, including ERALP (long-range surveillance radars), Kalkan (acquisition radars), AKR (fire-control radars), and MAR (mobile search radars for covering moving units). These integrated radars and sensors, supported by AI, construct a real-time “Recognised Air Picture” (RAP), facilitating quick decision-making. Most of them are already operational and integrated into the system.

Why does Türkiye need a Steel Dome?

Türkiye’s decision to develop its indigenous Steel Dome needs to be understood in the backdrop of growing regional security threats, shifting alliances, and advancing defence technology and air capabilities, all of which warrant careful analysis.

First, the nature of modern warfare is dominated by air and space technologies such as lethal drones and ballistic and cruise missiles supported by radars and satellite data. A classic example is Israeli air power demonstrated in the 1967 Six-Day War, when Israeli forces disabled much of the combined Arab air and ground capability within hours, decisively shaping the outcome of the conflict. The 2020 Azerbaijan-Armenia conflict has been described as the “first drone warfare” in modern history, as Azerbaijan’s use of Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones in Nagorno-Karabakh enabled Baku to neutralise Armenian tanks, artillery, and air defences. More recently, Israel’s war on Gaza and its military aggression against Iran, Hezbollah in Lebanon and airstrikes against Houthis in Yemen, besides the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war, underscore the centrality of air defence in both deterrence and combat effectiveness.

Second, Ankara’s zeal to achieve self-reliance. For most of its modern history, Türkiye has looked to the West for its security protection against its historical rival, Russia. The Cold War made Türkiye totally dependent on the West for arms imports, which faced a major debacle during the 1974 Cyprus crisis when Western nations imposed an arms embargo on Türkiye owing to Turkey’s intervention in Cyprus vis-à-vis the Greek coup to annex the Island. The event created a significant security gap for Türkiye, forcing it to either diversify its defence procurement (which was not possible at the time) or carve out a roadmap for manufacturing indigenous defence equipment instead of solely depending on foreign powers.

Third, it is Ankara’s S-400 dilemma. In 2019, Türkiye, a NATO member, purchased the Russian high-tech S-400 air defence system, prompting US sanctions and Ankara’s removal from the US-led F-35 stealth fighter jet programme. However, it came in the wake of the inefficiency of the US’s Patriot and THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defence) systems deployed by Saudi Arabia in intercepting Houthi drone and missile strikes from Yemen. Thereby, punishment by the West over defence diversification encouraged Ankara to produce its indigenous air defence architecture.

Fourth, the end of the Cold War and dissolution of the Soviet Union created an identity crisis for Türkiye in the Western Security Architecture. Ankara’s relevance to the West has repeatedly resurfaced, most recently in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. In search of an autonomous identity and ambitions to play a greater role as a regional middle power, the Erdoğan administration has been determined to secure its strategic autonomy from the West, incentivising it to advance its defence framework. Steel Dome thus provides Ankara with much-needed strategic independence in the region.

Fifth, Türkiye’s political geography, situated at the intersection of cultural, political, and ideological fault lines, necessitates its involvement and a greater role in its surroundings, rendering it vulnerable in the conflict-prone region. Russian projection of power in the Black Sea and Caucasus, state-building chaos in Syria in the aftermath of the Assad regime, the presence of Kurdish militia around southern borders, the Israel–Palestine conflict, and hostilities with Cyprus and Greece; all have a spillover effect in the region, requiring Ankara to have a multilayered system capable of responding to diverse threats from state and non-state actors.

Growing Israeli Threat

For decades, Israel has exercised superiority as the region’s most advanced air power. It solidified its hegemony, particularly with the deployment of the Iron Dome in 2011, which proved to be a benchmark for modern missile defence systems. Israel’s layered missile defence architecture includes the Iron Dome for short-range rockets and drones, David’s Sling for medium-range threats, and the Arrow II/III systems, supplemented by US support systems such as THAAD on a case-by-case basis. However, repeated barrages of rockets, drones, and missiles have tested the system, revealing certain operational limitations. Lately, it failed to intercept a lot of missiles coming from Hamas and Hezbollah, particularly Iran’s Fateh-110 and Shahab-series ballistic missiles. This display of vulnerability has emboldened many actors in the region, including Türkiye.

On the other hand, since Oct 7, Israel’s reckless and irresponsible attacks on Hamas leadership in foreign territories, notably the recent attack on Qatar, a major non-NATO ally, have undermined its sovereignty, warning against dependence on the West against Israeli aggression. Israeli actions in previous years suggest it has been actively seeking to expand this conflict by dragging in others, friends and foes. Likewise, the feud between Tel Aviv and Ankara, notably after the Mavi Marmara incident of 2010, and President Erdoğan’s vocal opposition to Israeli actions in the region, necessitate the advancement of Ankara’s air defence capability, particularly due to the non-reliability of NATO in case of Israeli attacks. Therefore, by branding its system as “Steel Dome”, Ankara is not only explicitly rivalling its Israeli counterpart but also aiming for superior air defence capabilities to contain Israel’s expansionist project. Thus, the Steel Dome symbolises a tectonic change in Türkiye’s defence trajectory and capabilities.

The Road Ahead

There is no doubt that Türkiye, under Erdoğan, has bolstered its domestic defence manufacturing. Nevertheless, the Steel Dome has indeed a long way to go. It has to be tested to establish its credibility, particularly about covering Türkiye’s vast geography. Moreover, the heavily capital-intensive air defence project might be affected by Türkiye’s low economic growth and budget constraints. Furthermore, the Steel Dome may face stiff competition from other actors, especially the USA’s Golden Dome project—a space-based air defence system for missile interception. Similarly, the Steel Dome’s technological maturity may face hurdles from new-age technologies, particularly hypersonic missiles, as well as the limitations inherent in relying on fully indigenous technology. Regardless, reducing Ankara’s external dependencies, the steel Dome ensures Türkiye’s strategic autonomy in an uncertain geopolitical environment. It also provides potential leverage to extend its defence architecture to allies under its security umbrella; it might be a game-changer in the region.