For decades, Iran insisted it did not seek nuclear weapons. In 2003, the country’s current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, issued an oral fatwa (religious decree) declaring weapons of mass destruction, both nuclear and chemical, forbidden (haram) in Islam. This was not merely “rhetorical”. In Shia jurisprudence, particularly Twelver usulis, a fatwa from a recognised mujtahid (a high-ranking jurist) is binding. Hence, the words from Ali Khamenei, who holds both religious and political authority, hold obligatory value. From Iran’s perspective, this was a clear message to the world that its nuclear ambitions were solely aimed at civilian applications.

But in a world where such assurances from leaders on the ‘wrong side’ of the West, and a Muslim conservative one at that, are rarely acknowledged or appreciated, the fatwa carried little weight in Western capitals. Washington, European capitals, along with Tel Aviv, have recurrently dismissed Khamenei’s religious pronouncements as a tactical ruse to mask the nuclear weapons programme. Tehran, they argued, could not be trusted because of its explicit support for Palestinian statehood, non-recognition of Israel, and patronising the Axis of Resistance, which included Israel’s regional state and non-state nemesis.

As a result, Iran, which endured its post-1979 revolution years under US sanctions, faced more most stringent ones in the last two decades. These were imposed not only by the Americans but also by the European Union and the United Nations. What this sanctions regime did was to throttle Iran’s economy, with its oil exports, the mainstay of its revenue, shrinking exponentially. Additionally, its currency devalued substantially over the years, with ordinary Iranians suffering the most as unemployment levels surged and prices of basic essentials skyrocketed, both literally and figuratively.

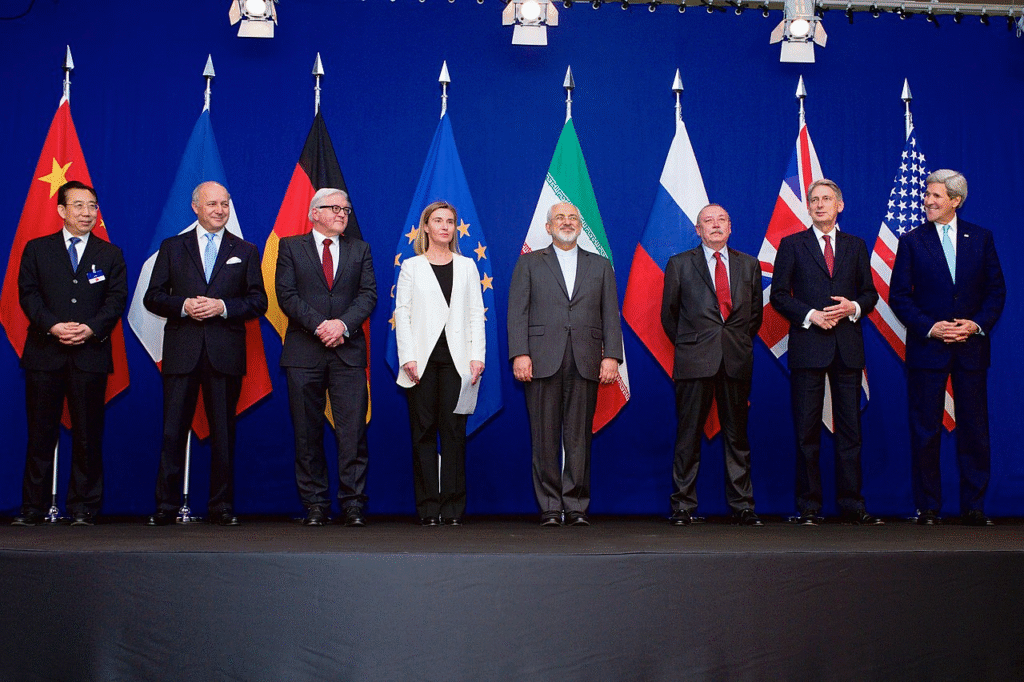

Even with its harsh isolation, Iran did choose diplomacy over confrontation, notwithstanding its uncompromising stances during the tenure of former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and his US counterpart, George W Bush, in the mid-2000s. But then, after years of tensions, diplomacy did find its way with US President Barack Obama and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, despite pressure from many quarters, bringing their countries to the multilateral negotiations table. As a result, in 2015, it signed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with the P5+1 (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Germany) under the auspices of the UN Security Council.

It may be recalled that despite pushback from hardliners in Tehran, President Rouhani’s administration agreed to tight limits on the country’s uranium enrichment activities and subject its nuclear facilities to the intrusive inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Even on the American side, many republican hawks, along with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, accused the Obama administration of giving too many economic concessions for so few technical limitations on Iran’s nuclear programme. Nevertheless, experts saw the deal conditions as a strong barrier to Iran’s path to a bomb. It not only cut down Iran’s enriched uranium stockpile but also set a cap on its enrichment levels at 3.67 per cent, well under the weapons-grade threshold.

Interestingly, even after the Trump administration pulled out of this multilateral agreement in 2018 and slapped on some tough sanctions, Iran remained broadly compliant for over a year as verified by the IAEA recurrently. The IAEA confirmed this compliance time and again, as Iran held out hope that the European signatories of the JCPOA would keep their promises. However, that never happened as the Europeans chose a wait-and-watch policy rather than engaging Tehran. As Iran faced economic strangulation and diplomatic abandonment, the country, as reports suggested, gradually reduced its compliance under the JCPOA by starting to enrich uranium to higher levels, albeit still below weapons-grade. This was seen as a pressure tactic to get the Western JCPOA signatories to fulfil their deal commitments.

Then came the war that changed everything. On June 13, Israel, the Middle East’s only nuclear weapons power, launched unprovoked airstrikes against Iran’s nuclear and military sites, along with killing several of its top military commanders and nuclear scientists, with ‘express’ American support. Over 12 days, the US joined the strikes, targeting critical facilities of Fardow, Natanz and Isfahan, with bunker-busting bombs to “obliterate” the Iranian nuclear programme. Contrary to Trump’s claims, US intelligence assessments of the damage at Iranian nuclear sites have speculated that the most these airstrikes did was to set back the programme by a few months.

The strikes were not provoked by any imminent Iranian attack on either Israel or US interests in the region. Nor were they a response to a breach of any nuclear non-proliferation obligation under the IAEA framework. Instead, these were justified as “pre-emptive” moves by Israel so as to ensure Iran never gets close to a nuclear weapon. This is the same logic that Israel, aided by the United States, has deployed before, notably in Iraq in 1981 and Syria in 2007. But unlike Iraq and Syria, Iran is not a nascent nuclear aspirant with one or two vulnerable facilities. It is a technologically astute country with decades of expertise and a dispersed, hardened nuclear know-how, if not infrastructure.

After nearly two weeks of fighting, the ceasefire announced by Donald Trump holds, for now. Yet, rather than obliterating Iran’s nuclear programme, the strikes have made a far stronger case for the clerical regime in Tehran to pursue nuclear weapons. Therefore, the very logic that drove Israel to attack, that the nuclear weapons deter enemies, may now appear compelling to Iran’s security establishment, which would be reflecting on the country’s wartime performance of its defensive and offensive capabilities.

For ordinary Iranians, the war has brought both anger and anxiety. They are angry at their country being attacked without provocation, and anxious over what may come next in this region of predictable unpredictabilities. While many were already frustrated with their government’s economic mismanagement and authoritarian clampdowns of years, these indiscriminate bombings by foreign powers, killing hundreds of civilians, reignited nationalist sentiments. Contrary to Israeli and American notions that its indiscriminate attacks on civilian and non-civilian targets will generate some sort of internal crisis for the clerical regime, it reminded Iranians across the ideological divide that, regardless of domestic grievances, an external threat has a unifying effect.

Consequently, the paradox is bitter as by attacking Iran’s nuclear facilities to prevent it from acquiring a nuclear weapons technology, Israel and the United States may have given Tehran every strategic reason to build a bomb.

For now, Iran’s nuclear doctrine remains officially restrained by Khamenei’s fatwa, which describes the pursuit, development, and use of weapons of mass destruction as haram. But the supreme leader is 86 years old. His health is frail, and succession is looming large in Iran’s political landscape. While his successor may uphold the fatwa, it is equally plausible that the next supreme leader rescinds it in the name of national security.

If that happens, it would mark a historic shift in Iran’s ideological self-conception itself. Since the 1979 revolution, the Islamic Republic has presented itself as a moral state, distinct from the world’s cynical powers. The restrain against nuclear weapons and support for the oppressed has been central to this identity, with a claim that Iran’s power rests on faith, resilience, and regional alliances rather than a nuclear deterrent.

But faith and morality rarely suffice in an international order structured by raw power. Take the contrast of North Korea and Iraq, both of which started pursuing their nuclear programmes in the second half of the 20th century. North Korea defied every sanction and diplomatic isolation effort to build its bomb, finally testing one in 2006. Today, its regime remains in place, untouched by US or South Korean military power. On the other hand, after its Osiraq nuclear facility was bombed by Israel in 1981, even before its commissioning, Iraq effectively abandoned its programme after the first Gulf War. What followed was an invasion and occupation in 2003 on the pretext of non-existent weapons of mass destruction, an event from which the region is yet to re-emerge.

Iran’s leaders are smart when it comes to global power politics, and they understand the lessons of history. If the possession of nuclear weapons guarantees security, then the logic of deterrence becomes irresistible, especially after being attacked precisely for not having a bomb. Iran’s hardliners, long sceptical of engagement with the West, feel vindicated. While it is possible that Iranian leadership may still work out a deal with the United States, as Donald Trump believes, will the Revolutionary Guards forego the prospect of a bomb, particularly after the country’s air defence system was crippled by Israel with near total control over its airspace.

The tragedy is that this was preventable. In 2015, the world had an agreement that worked. Iran’s nuclear programme was under the tightest inspections regime ever implemented. There were no bombings, no looming threat of war, and Iran’s moderate camp under President Rouhani could at least argue that diplomacy brought results. But the American withdrawal from the deal, the subsequent sanctions, and now direct strikes have destroyed that argument. This has only narrowed the space for those (Reformist bloc) seeking pragmatic engagements with the West while emboldening the conservatives in Tehran.

The road ahead is bleak. It is unlikely Iran will sprint towards a bomb tomorrow. There are still domestic debates and religious cum legal hurdles. But the seed of nuclear ambition has been firmly planted by those who sought to destroy it. The moment the Iranian clerical regime feels that the survival of the Islamic Republic depends on nuclear deterrence, it is highly unlikely that any fatwa will stop it from crossing the threshold then.

When that day comes, Washington and Tel Aviv will have to reckon with the consequences of their own choices. A nuclear Iran would fundamentally change the security landscape of the Middle East by sparking proliferation with Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt to seek nuclear capabilities of their own. It may be remembered that the Saudis have consistently warned that they will consider their nuclear options should Tehran develop a weapon.

More than that, this reality will also mark the ultimate failure of a policy driven by coercion and violence rather than respect, dialogue, and trust-building. For over three decades, Iran tried to argue that its faith forbade nuclear weapons. The world, the western world per se, has responded with disbelief, sanctions, and war. And so, paradoxically, it may be the clerical regime’s own survival instinct, triggered by these very actions, that pushes it towards the bomb.

If that happens, history will record that Iran was forced into becoming precisely what its enemies accused it of being.